- Joined

- Mar 11, 2013

- Messages

- 17,047

- Reputation

- 5,639

- Reaction score

- 54,715

- Points

- 0

- Currently Smoking

- fine-ass '22 harvest!

>> original site, with a good video...

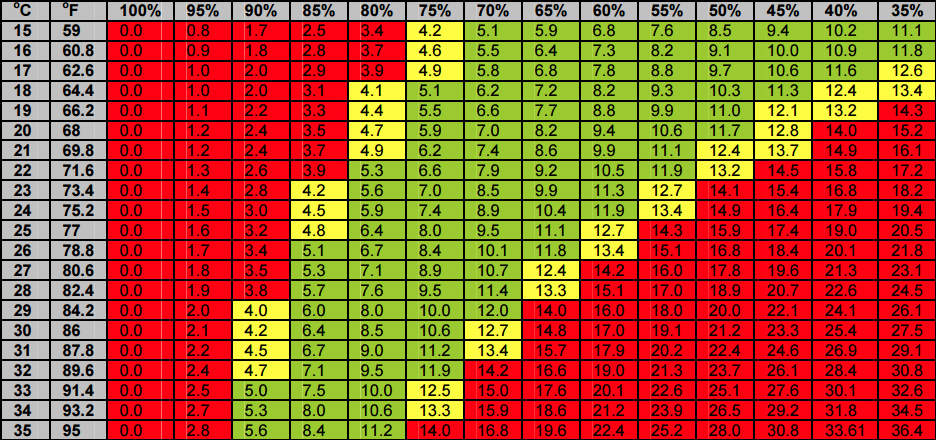

>>> here's a chart... google will show several others...

* RH% across the top here--> This chart is in hectopascals, not kilopascals (Kpa) like below; move decimal to left 1..

diagnostics Quick reference chart:

diagnostics Quick reference chart:Low VPD / High RH: Mineral deficiencies; Guttation (this is it)-->

High VPD / Low RH: Wilting; Leaf roll; Stunted plants; Leathery/crispy leaves

Vapor Pressure Deficit - The Hidden Force on your Plants

Vapor Pressure Deficit - The Hidden Force on your Plants Once you understand what vapor pressure deficit is, all those environmental factors you're trying to juggle in your mind suddenly click into place and you start to think and feel like a plant. Take a few minutes to understand why VPD management is key to creating the perfect indoor growing environment! Your plants will thank you for it!

Humidity is HUGE when it comes to growing plants. An important milestone in becoming a competent and responsive grower is developing an understanding of what humidity is, how plants respond to it, and how you can manage and manipulate it.

Firstly, let's make sure we're all on the same page. When we speak of the "humidity" of or in the air we are basically referring to the amount of water in the air. "In the air?" What do we mean? Well, water can only truly stay in the air when it is in gas form - aka "water vapor". We're not talking about tiny droplets of water in the air here (e.g. fog or mist.)

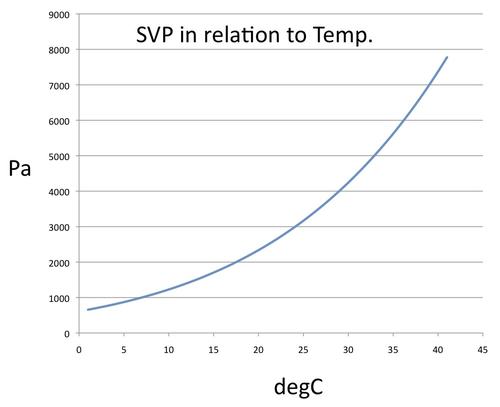

Unsurprisingly, temperature plays a crucial role when it comes to humidity. The warmer the air, the more water vapor it can potentially hold. As the amount of water air can hold constantly changes with temperature it can be difficult to get a handle on what we need to measure. Fortunately, an answer comes in the form of the concept of "Relative Humidity" (RH) - this is a measurement in terms of percentage, of the water vapor in the air compared to the total water vapor potential that the air could hold at a given temperature. So, when we say there's a relative humidity of 50% - we mean "At this specific temperature, the air is carrying half the potential water vapor possible."

The Effect of Relative Humidity on Your Plants

RH can be easily measured using digital or analogue meters called "hygrometers." They are available for around $15 at your local indoor gardening store. But what do the readings mean for your plants?

Turns out-they mean a great deal! While many novice growers focus solely on keeping temperature in range, many take their eye off the ball as far as RH is concerned-perhaps because they don't fully understand what it is or how to manipulate it to their advantage.

Have you ever been to Florida in July? You'll know that it's not just the heat that's oppressive, it's the humidity! You feel constantly wet with sweat - the whole place feels like a sauna you can't escape from! (Sorry Floridians!)

RH has an ever more direct effect on plants. Plants need to "sweat" too - or rather, they need to transpire (release water vapor through their stomata) in order to grow. The amount of water plants lose through transpiration is regulated, to a point, by opening and closing their stomata. However, as a general rule, the drier the air, the more plants will transpire.

Under Pressure

All gasses in the air exert a certain "pressure." The more water vapor in the air the greater the vapor pressure. What does this mean? Well, in high RH conditions (think of Florida again) there is a greater vapor pressure being exerted on plants than in low RH conditions. From a plant's perspective, high vapor pressure can be thought of as an unseen force in the air pushing on the plants from all directions. This pressure is exerted onto the leaves by the high concentration of water vapor in the air making it harder for the plant to 'push back' by losing water into the air by transpiration. This is why with high RH plants transpire less. Conversely, in environments with low RH, only a small amount of pressure is exerted on the plants' leaves, making it easy for them to lose water into the air.

What is Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD)?

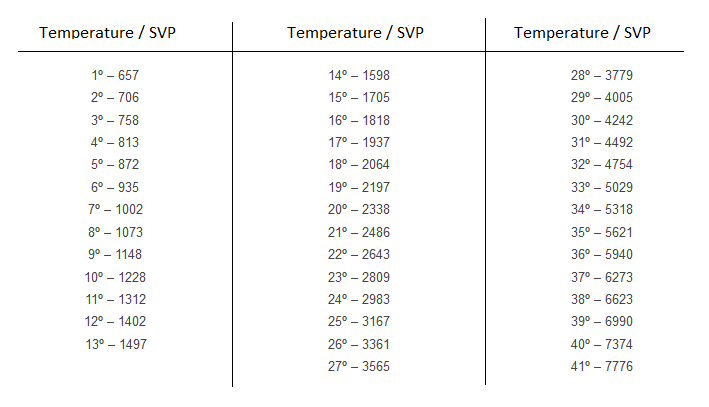

Okay, so now that you have RH firmly implanted into your conceptual map, we move on to Vapor Pressure Deficit or VPD. As implied by the word "deficit" we're talking about the difference between two things. In this case, it's the difference between the theoretical pressure exerted by water vapor held in saturated air (100% RH at a given temperature) and the pressure exerted by the water vapor that is actually held in the air being measured at the same given temperature.

An easy way to understand vapor pressure deficit.

The VPD is currently regarded of how plants really 'feel' and react to the humidity in the growing environment. From a plant's perspective the VPD is the difference between the vapor pressure inside the leaf compared to the vapor pressure of the air. If we look at it with an RH hat on; the water in the leaf and the water and air mixture leaving the stomata is (more often than not) completely saturated -100% RH. If the air outside the leaf is less than 100% RH there is potential for water vapor to enter the air because gasses and liquids like to move from areas of high concentration (in this example the leaf) into areas of lower concentration (the air). So, in terms of growing plants, the VPD can be thought of as the shortage of vapor pressure in the air compared to within the leaf itself.

Another way of thinking about VPD is the atmospheric demand for water or the 'drying power' of the air. VPD is usually measured in pressure units, most commonly millibars or kilopascals, and is essentially a combination of temperature and relative humidity in a single value. VPD values run in the opposite way to RH vales, so when RH is high VPD is low. The higher the VPD value, the greater the potential the air has for sucking moisture out of the plant. As mentioned above, VPD provides a more accurate picture of how plants feel their environment in relation to temperature and humidity which gives us growers a better platform for environmental control. The only problem with VPD is it's difficult to determine accurately because you need to know the leaf temperature. This is quite a complex issue as leaf temperature can vary from leaf to leaf depending on many factors such as if a leaf is in direct light, partial shade or full shade. The most practical approach that most environmental control companies use to assess VPD is to take measurements of air temperature within the crop canopy. For humidity control purposes it's not necessary to measure the actual leaf VPD to within strict guidelines, what we want is to gain insight into is how the current temperature and humidity surrounding the crop is affecting the plants. A well-positioned sensor measuring the air temperature and humidity close to, or just below, the crop canopy is adequate for providing a good indication of actual leaf conditions.

Managing Humidity

Managing the humidity in your indoor garden is essential to keep plants happy and transpiring at a healthy rate. Transpiration is very important for healthy plant growth because the evaporation of water vapor from the leaf into the air actively cools the leaf tissue. The temperature of a healthy transpiring leaf can be up to 2-6°C lower than a non-transpiring leaf, this may seem like a big temperature difference but to put it into perspective around 90% of a healthy plant's water uptake is transpired while only around 10% is used for growth. This shows just how important it is to try and control your plants environment to encourage healthy transpiration and therefore healthy growth. So what should you aim to keep your humidity at? Many growers say a RH of 70% is good for vegetative growth and 50% is good for generative (fruiting /flowering) growth. This advice can be followed with some degree of success but it's not the whole story as it fails to take into account the air temperature.

***( I'm unsure what to make of these two charts here, vs.the others I see which give no info about leaf temp.differences from the air? ... these didn't blow up right anyway,..)

If your growing environment runs on the warm side during summer, like many indoor growers, a RH of 75% should be maintained for temperatures between 79-84°F (26-29°C.)

The problem with running a high relative humidity when growing indoors it that fungal diseases can become an issue and carbon filters become less effective. It is commonly stated that above 60% RH the absorption efficiency drops and above 85% most carbon filters will stop working altogether. For this reason it is good practice to run your RH between 60-70% with the upper temperature limit depending on your crop's ideal VPD range, in the example it would be 64-79°F (18-26°C.)

The table also shows that if your temperature is above 72°F (22°C), 50% RH becomes critically low and should generally be avoided to minimize plant stress. Please understand that by presenting this information we do not want you to go to your indoor gardens and run your growing environment to within strict VPD values. What's important to take from this is that VPD can help you provide a better indication of how much moisture the air wants to pull from your plants than RH can. If you want to work out for yourself the VPD of your plants leaves you can follow the steps below:

See how the vapor pressure deficit changes when there is a smaller gap between air temperature and leaf temperature.

Humidity's Effect on Plants

Plants cope with changing humidity by adjusting the stomata on the leaves. Stomata open wider as VPD decreases (high RH) and they begin to close as VPD increases (low RH). Stomata begin to close in response to low RH to prevent excessive water loss and eventually wilting but this closure also affects the rate of photosynthesis because CO2 is absorbed through the stomata openings. Consistently low RH will often cause very slow growth or even stunting. Humidity therefore indirectly affects the rate of photosynthesis so at higher humidity levels the stomata are open allowing CO2 to be absorbed.

Thai basil leaves curling due to localized low humidity stress caused by T5 fluorescent lighting being too low

When humidity gets too low plants will really struggle to grow. In response to high VPD plants will try to stop the excessive water loss from their leaves by trying to avoid light hitting the surface of the leaf. They do this by rolling the leaf inwards from the margins to form tube like structures in an attempt to expose less of the leaf surface to the light, as shown in the photo.

For most plants, growth tends to be improved at high RH but excessive humidity can also encourage some unfavorable growth attributes. Low VPD causes low transpiration which limits the transport of minerals, particularly calcium as it moves in the transpiration stream of the plant - the xylem. If VPD is very low (95-100% RH) and the plants are unable to transpire any water into the air, pressure within the plant starts to build up. When this is coupled with a wet root zone, which creates high root pressure, it combines to create excessive pressure within the plant which can lead to water being forced out of leaves at their edges in a process called guttation. Some plants have modified stomata at their leaf edges called hydathodes which are specially adapted to allow guttation to occur. Guttation can be spotted when the edges of leaves have small water droplets on, most evident in early morning or just after the lights have come on. If you see leaves that appear burnt at the edges or have white crystalline circular deposits at the edges it could be evidence that guttation has occurred.

Tomato plants exhibiting the phenomenon of guttation due to excessively high relative humidity levels.

Most growers are well aware that with high humidity comes and increased risk of fungal diseases. Water droplets can form on leaves when water vapor condenses out of the air as temperature drops, providing the perfect breeding ground for diseases like botrytis and powdery mildew. If humidity remains high it further promotes the growth of fungal diseases. The water droplet exuded through guttation also creates the perfect environment for fungal spores to germinate inviting disease to take hold.

Powdery mildew takes hold due to poor daytime / nighttime relative humidity control

Quick reference chart:

Quick reference chart:Low VPD / High RH: Mineral deficiencies; Guttation; Disease; Soft growth

High VPD / Low RH: Wilting; Leaf roll; Stunted plants; Leathery/crispy leaves

*(Words: Gareth Hopcroft and Everest Fernandez )

Last edited:

. As you said

. As you said  . Anyway, crucial information I would say,, especially if you want to be a better "gardener" :smoking:.

. Anyway, crucial information I would say,, especially if you want to be a better "gardener" :smoking:. .

. .... I'm learning too,... Being and OD grower mainly, all this is out of my hands usually! But for Sick Bay diagnostics, it's definitely helped me pin down the "why's" behind some more difficult to figure out problems,...

.... I'm learning too,... Being and OD grower mainly, all this is out of my hands usually! But for Sick Bay diagnostics, it's definitely helped me pin down the "why's" behind some more difficult to figure out problems,... ... I'll be tweaking this a bit as I lean more,... there are PITA calculations (in the video) to make if you really want to get scientific about it, and you'll need and IR thermometer to take leaf surface temps (another variable PITA, as it will be different location to location; top exposed leaves probably the best place).... But in practical application,

... I'll be tweaking this a bit as I lean more,... there are PITA calculations (in the video) to make if you really want to get scientific about it, and you'll need and IR thermometer to take leaf surface temps (another variable PITA, as it will be different location to location; top exposed leaves probably the best place).... But in practical application,

.......(video has the equations).... I don't what to make of this.....

.......(video has the equations).... I don't what to make of this.....