forgive me, i was not saying JM is a troll. unless he was the guy saying gravity pushes and doesnt pull. all comments directed at JM were in the last paragraph alone.

and i'll leave you all with this by the way because i think it is pertinent to the discussion of net energy gain

OH Danny Boy... me Irish eyes are smilin on ya!  see below... its been almost a year and I'm no quantum physics major... forgive me for mis-explaining the gravity thing...while you read this please consider.... the current "laws of physics" assume time and space are constants... if you consider that time and space may be variable... then perhaps energy is there we cant see with current (traditional scientific instrumentation)

...

see below... its been almost a year and I'm no quantum physics major... forgive me for mis-explaining the gravity thing...while you read this please consider.... the current "laws of physics" assume time and space are constants... if you consider that time and space may be variable... then perhaps energy is there we cant see with current (traditional scientific instrumentation)

...

Ripples in Spacetime

What are Gravitational Waves?

Predicted in

Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, gravitational waves are disturbances in the curvature of spacetime caused by the motions of matter. Propagating at (or near) the speed of light, gravitational waves do not travel "through" spacetime as such -- the fabric of spacetime itself is oscillating. Though gravitational waves pass straight t hrough matter, their strength weakens proportionally to the distance traveled from the source. A gravitational wave arriving on Earth will alternately stretch and shrink distances, though on an incredibly small scale -- by a factor of

for very strong sources. That's roughly equivalent to measuring a change the size of an atom in the distance from the Sun to Earth! No wonder these waves are so hard to detect.

Are Gravitational Waves Real?

The first test of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity (

the bending of light by the gravity of a large mass, seen in a solar eclipse) was made by a team led by Sir Arthur Eddington, who became one of the strongest supporters of the new theory. But when it came to gravity wave s, Eddington was skeptical and reportedly commented, "Gravitational waves propagate at the speed of thought."

Ed Seidel, NCSA/Univ. of Illinois, on-camera

QuickTime Movie

QuickTime Movie (1.0 MB);

Sound File (615K);

Text

Eddington was not the only skeptic. Many physicists thought the waves predicted by the theory were simply a mathematical artifact. Yet others continued to further develop and test the concept. By the 1960s, theorists had showed that if an object emits gravitational waves, its mass should decrease. Then, in the mid 1970s, American researchers observed a

binary pulsar system (named PSR1913+16) that was thought to consist of two

neutron stars orbiting each other closely and rapidly. Radio pulses from one of the stars showed that its orbital period decreases by 75 microseconds per year. In other words, the stars are spiralling in towards each other -- and by just the amount predicted if the system were losing energy by radiating gravity waves.

Why Should We Care About Gravity Waves?

Gravitational wave astronomy could expand our knowledge of the cosmos dramatically. For starters, gravitational waves, though weakening with distance, are thought to be unchanged by any material they pass through and, therefore, should carry signals unalt ered across the vast reaches of space. By comparison, electromagnetic radiation tends to be modified by intervening matter. Aside from demonstrating the existence of black holes and revealing a wealth of data on supernovae and neutron stars, gravitational wave observations could also provide an independent means of estimating cosmological distances and help further our understanding of how the

universe came to be the way it looks today and of its ultimate fate. Gravitational waves might unveil phenomena never considered before. Nature is smarter than any theorist trying to imagine or calculate what might be out there!

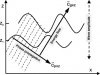

Sifting Through the Waves

From

supercomputer simulations performed at NCSA and other advanced computational facilities, relativity researchers expect different types of cosmic events to possess characteristic gravitational wave signatures. Consider the waves emitted by a single, distorted black hole, for example.

Distorted Black Hole

The remarkable thing about a black hole when simulated on a computer is that no matter how it forms or is perturbed, whether by infalling matter, by gravitional waves, or via a collision with another object (including a second black hole), it will "ring" with a unique frequency known as its

natural mode of vibration. It's this unique wave signature that will allow scientists to know if they've really detected a black hole. But that's not all. The signal will tell them how big the black hole is and how fast it's spinning.

source:

http://archive.ncsa.illinois.edu/Cyberia/NumRel/GravWaves.html

yeah, why are we so special? lol

yeah, why are we so special? lol